- Home

- Richard Adams

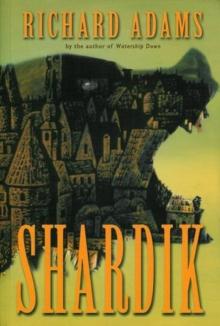

Shardik Page 6

Shardik Read online

Page 6

He fell into an uneasy, slightly feverish doze in which the happenings of the long day began to recur, dreamlike and confused. He imagined himself to be crouching once more in the canoe, listening to the knock and slap of water in the dark. But it was on the shendron's platform that he landed, and once again refused to tell what he had seen. The shendron grew angry and forced him to his knees, threatening him with his hot knife as the folds of his fur cloak rippled and became a huge, shaggy pelt, dark and undulant as a cypress tree.

"By the Bear!" hissed the Baron. "You will no longer choose!"

"I can speak only to the Tuginda!" cried the hunter aloud.

He started to his feet, open-eyed. Before him on the checkered pavement was standing a woman of perhaps forty-five years of age. She had a strong, shrewd face and was dressed like a servant or a peasant's wife. Her arms were bare to the elbow and in one hand she was carrying a wooden ladle. Looking at her in the starlight, he felt reassured by her homely, sensible appearance. At least there was evidently cooking in this island of sorcery, and a straightforward, familiar sort of person to do it. Perhaps she might have some food to spare.

"Crendro" (I see you), said the woman, using the colloquial greeting of Ortelga.

"Crendro," replied the hunter.

"You have come down the Ledges?" asked the woman.

"Yes."

"Alone?"

"The priestess and the High Baron of Ortelga are following--at least, so I hope." He raised one hand to his head. "Forgive me. I'm tired out and my shoulder's painful."

"Sit down again." He did so.

"Why are you here--on Quiso?"

"That I must not tell you. I have a message--a message for the Tuginda. I can tell it only to the Tuginda."

"Yourself? Is it not for your High Baron, then, to tell the Tuginda?"

"No. It is for myself to do so." To avoid saying more, he asked, "What is this stone?"

"It's very old. It fell from the sky. Would you like some food? Perhaps I can make your shoulder more comfortable."

"It's good of you. I'd like to eat, and to rest too. But the Tuginda--my message--"

"It will be all right. Come this way, with me."

She took him by the hand and at the same moment he saw the priestess and Bel-ka-Trazet approaching over the bridge. At the sight of his companion the High Baron stopped, bent his head and raised his palm to his brow.

8 The Tuginda

IN SILENCE THE HUNTER allowed himself to be led across the circle and past the iron brazier, in which the fire had sunk low. He wondered whether it too had been lit for a signal and had now served its turn, for there seemed to be none to keep it burning. Overtaking them, the Baron spoke no word, but again raised his hand to his forehead. It shook slightly and his breathing, though he controlled it, was short and unsteady. The hunter guessed that the descent of the steep, slippery Ledges had taxed him more than he cared to show.

They left the fire, ascended a flight of steps and stopped before the door of a stone building, its handle a pendent iron ring made like two bears grappling each with the other. Kelderek had never before seen workmanship of this kind and watched in wonder as the handle was turned and the weight of the door swung inward without sagging or scraping against the floor within.

Crossing the threshold, they were met by a girl dressed like those who had tended the cressets on the terrace. She was carrying three or four lighted lamps on a wooden tray which she offered to each of them in turn. He took a lamp but still saw little of what was around him, being too fearful to pause or stare about. From somewhere not far away came a smell of cooking and he realized once again that he was hungry.

They entered a firelit, stone-floored room, furnished like a kitchen with benches and a long, rough table. The hearth, set in the wall, had a cowled chimney above and an ash pit below, and here a second girl was tending three or four cooking pots. The two exchanged a few words in low voices and began to busy themselves about the hearth and table, from time to time glancing sideways at the Baron with a kind of shrinking fascination.

Since they had left the paved circle the hunter had been overcome by the knowledge that he had committed sacrilege. Clearly, the stone on which he had sat was sacred. Had he not indeed been told that it had fallen from the sky? And the woman--the homely woman with the ladle--she could be only--

As she approached him in the firelight he turned, trembling, and fell upon his knees.

"Saiyett--I--I was not to know--"

"Don't be afraid," she said. "Lie down here, on the table. I want to look at your shoulder. Melathys, bring some warm water; and, Baron, will you please hold one of the lamps close?"

As they obeyed her, the Tuginda unlaced the hunter's jerkin and began to wash the clotted blood from the gash in his shoulder. She worked carefully and deliberately, cleaned the wound, dressed it with a stinging, bitter-scented ointment and finally bound his shoulder with a clean cloth. From behind the lamp the Baron's disfigured face looked down at him with an expression which made him prefer to keep his eyes shut.

"Now we will eat--and drink too," said the Tuginda at last, helping him to his feet, "and you girls may go. Yes, yes," she added impatiently to one who was lifting the lid from the stew pot and lingering by the fire, "I can ladle stew into bowls, believe it or not."

The girls scurried out and the Tuginda, picking up her ladle, stirred the various pots and filled four bowls from them. Kelderek ate apart, standing up, and she did nothing to dissuade him, herself sitting on a bench by the hearth and eating slowly and little, as though to make sure that she would finish no sooner and no later than the rest. The bowls were wooden, but the cups into which Melathys poured wine were of thin bronze, six-sided and flat-based, so that, unlike drinking horns, they stood unsupported without spilling. The cold metal felt strange to the hunter's lips.

When the two men had finished, Melanthys brought water for their hands, took away the bowls and cups and made up the fire. The Baron, with his back against the table, sat facing the Tuginda, while the hunter remained standing in the shadows beyond.

"I sent for you, Baron," began the Tuginda. "As you know, I asked you to come here tonight."

"You have put me to indignity, saiyett," replied the Baron. "Why was the fear of Quiso unloosed upon us? Why must we have lain bemused in darkness upon the shore? Why--"

"Was there not a stranger with you?" she answered, in a tone which checked him instantly, though his eyes remained fixed upon hers. "Why do you suppose you could not reach the landing place? And were you not armed?"

"I came in haste. The matter escaped me. But in any case, how could you have known these things, saiyett?"

"No matter how. Well, the indignity, as you call it, is ended now. We will not quarrel. The girls who carried my message to Ortelga--they have been looked after?"

"It is hard to reach Ortelga against the current. They were tired. I said they should remain there to sleep."

She nodded.

"My message, as I suppose, was unexpected, and you have made me an unexpected reply, bringing me a wounded man whom I find sitting alone and exhausted on the Tereth stone."

"Saiyett, this man is a hunter--a simple fellow whom they call--"

He stopped, frowning.

"I know of him," she said. "On Ortelga they called him Kelderek Play-with-the-Children. Here he has no name, until I choose."

Bel-ka-Trazet resumed.

"He was brought to me tonight on his return from a hunting expedition, having refused to tell one of the shendrons whatever it was that he had seen. At first I treated him with forbearance, but still he would say nothing. I questioned him and he answered me like a child. He said, 'I have found a star. Who will believe that I have found a star?' Then he said, 'I will speak only to the Tuginda.' At this I threatened him with a heated knife, but he answered only, 'It must be as God wills.' And then, in this very moment, saiyett, arrived your message. 'So,' thought I, 'this man, who has said that he will speak only to you--who

ever heard a man say this before?--let us take him at his word, if only to make him speak. He had better come to Quiso too--to his death, as I suppose, which he has brought upon himself.' And then he sits down upon the Tereth stone, God help us! And we find him face to face and alone with yourself. How can he return to Ortelga? He must die."

"That is for me to say, while he remains on Quiso. You see much, Baron, and you guard the people as an eagle her brood. You have seen this hunter and you are angry and suspicious because he has defied you. Have you seen nothing else from your eyrie on Ortelga this two days past?"

It was plain that Bel-ka-Trazet resented being questioned, but he answered civilly enough.

"The burning, saiyett. There has been a great burning."

"For leagues beyond the Telthearna the jungle has burned. All yesterday it rained ashes in Quiso. During the night, animals came ashore from the river--some of kinds never seen here before. A makati comes tame as a cat to Melathys, begging for food. She feeds it and then, following it to the water, finds a green snake coiled about the Tereth. Of whom are these the forerunners? At dawn, the brook in the high ravine left its course and streamed down over the Ledges: but at the foot it gathered itself, flowed back into its channel and did no, harm. Why? Why were the Ledges washed, Baron? For the coming of your feet, or my feet? Or was it for the coming of some other feet? What messages, what signs were these?"

The Baron slid his tongue along the jagged edge of one lip and plucked the fur of his cape between his fingers, but answered nothing. The Tuginda turned to face the firelight and remained silent for some time. She sat perfectly still, her hands at rest in her lap, her composure like that of a tree when the wind has dropped. At length she said,

"So I ponder and pray and call upon such little wisdom as I may have acquired over the years, for I know no more than Melathys, or Rantzay or the girls what these things may mean. At last I send for you. Perhaps, it seems to me, you may be able to tell me something that you have seen or heard. Perhaps you may give me some clue.

"Meanwhile, if he should come, how should I receive him--he whom God means to send? Not with power or display, no, but as a servant. What else am I? So in case he should come, I dress myself like the ignorant, poor woman that God sees me to be. I know nothing, but at least I can cook a meal. And when the meal is ready I go out to the Tereth, to wait and pray."

Again she was silent. Melathys murmured,

"Perhaps the High Baron knows more than he has told us."

"I know nothing, saiyett."

"But it did not occur to me," went on the Tuginda, "that the stranger whom I knew to be with you--"

She broke off and looked across the room to where Kelderek was still standing by himself, away from the light. "So, hunter, you maintained to the High Baron's hot knife, did you, that you had a message for my ears alone?"

"It is true, saiyett," he answered, "and it is true also, as the High Baron says, that I am a man of no rank--one who gets his living as a hunter. Yet I knew--and know now--beyond doubt or gainsaying, that none must hear this news before yourself."

"Tell me, then, what you could not tell to the shendron or the High Baron."

He began to speak of his hunting expedition that morning and of the undergrowth full of bewildered, fugitive animals. Then he told of the leopard and of his foolhardy attempt to pass it and escape inland. As he spoke of his ill-aimed arrow, his panic flight and fall from the bank, he trembled and gripped the table to steady himself. One of the lamps had burned dry, but the priestess made no move and the wick remained smoking until it died.

"And then," said the hunter, "then there stood over me, where I lay, saiyett, a bear--such a bear as never was, a bear tall as a dwelling-hut, his pelt like a waterfall, his muzzle a wedge across the sky. The leopard was as iron on his anvil. Iron --no--ah, believe me!--when the bear struck him he became like a chip of wood when the axe falls. He spun through the air and tumbled like a pierced bird. It was the bear--the bear who saved me. He struck once and then he was gone."

The hunter paused and came slowly forward to the fire.

"He was no vision, saiyett, no fancy of my fear. He is flesh and bone--he is real. I saw the burns on his side--I saw that they hurt him. A bear, saiyett, on Ortelga--a bear more than twice as tall as a man!" He hesitated, and then added, almost inaudibly, "If God were a bear--"

The priestess caught her breath. The Baron stood up, tipping back the bench against the table as his hand clutched at his empty scabbard.

"You had better be plain," said the Tuginda in a calm, matter-of-fact tone. "What do you mean, and what is it that you are thinking about the bear?"

To himself the hunter seemed like a man setting down at last a heavy burden which he has carried for miles, through darkness and solitude, to the place where it must go. But more strongly still, he felt once again the incredulity which had filled him that morning on the lonely, upstream shore of Ortelga. How could it be that this was the appointed time, here the place and himself the man? Yet it was so. It could not be otherwise. His eyes met the shrewd, intent gaze of the Tuginda.

"Saiyett," he replied, "it is Lord Shardik."

There was dead silence. Then the Tuginda answered carefully, "You understand that to be wrong--to deceive yourself and others--would be a sacrilegious and terrible thing? Any man can see a bear. If what you saw was a bear, O hunter who plays with children, for God's sake say so now and return home unharmed and in peace."

"Saiyett, I am nothing but a common man. It is you that must weigh my tale, not I. Yet as I live, I myself feel certain that the bear that saved me was none other than Lord Shardik."

"Then," replied the Tuginda, "whether you are proved wrong or right, it is plain what we have to do."

The priestess was standing with palms outstretched and closed eyes, praying silently. The Baron, frowning, paced slowly across to the farther wall, turned and paced back, gazing down at the floor. As he reached the Tuginda she laid her hand upon his wrist and he stopped, looking at her from one half-closed and one staring eye. She smiled up at him, for all the world as though no prospect lay before them but what was safe and easy.

"I'll tell you a story," she said. "There was once a wise, crafty baron who pledged himself to guard Ortelga and its people and to keep out all that could harm them: a setter of traps, a digger of pits. He perceived enemies almost before they knew their own intents and taught himself to distrust the very lizards on the walls. To make sure that he was not deceived, he disbelieved everything--and he was right. A ruler, like a merchant, must be full of craft, must disbelieve more than half he hears, or he will be a ruined man.

"But here the task is more difficult. The hunter says, 'It is Lord Shardik,' and the ruler, who has learned to be a skeptical man and no fool, replies, 'Absurd.' Yet we all know that one day Lord Shardik is to return. Suppose it were today and the ruler were in error, then what an error that would be! All the patient work of his life could not atone for it."

Bel-ka-Trazet said nothing.

"We cannot take the risk of being wrong. To do nothing might well be the greatest sacrilege. There is only one thing we can do. We must discover beyond doubt whether this news is true or false; and if we lose our lives, then God's will be done. After all, there are other barons and the Tuginda does not die."

"You speak calmly, saiyett," replied the Baron, "as though of the tendriona crop or the coming of the rains. But how can it be true--"

"You have lived long years, Baron, with the Dead Belt to strengthen today and the tax to collect tomorrow. That has been your work. And I--I too have lived long years with my work--with the prophecies of Shardik and the rites of the Ledges. Many times I have imagined the news coming and pondered on what I should do if ever it were to come indeed. That is why I can say to you now, 'The hunter's tale may be true,' and yet speak calmly."

The Baron shook his head and shrugged his shoulders, as though unwilling to argue.

"Well, and what are we to do?" he asked.

>

"Sleep," she replied unexpectedly, going to the door. "I will call the girls to show you where."

"And tomorrow?"

"Tomorrow we will go upstream."

She opened the door and struck once upon a bronze gong. Then she returned and, going across to Kelderek, laid her hand on his sound shoulder.

"Good night," she said, "and let us trust that it may indeed be that good night that the children are taught to pray for."

9 The Tuginda's Story

THE NARROW PASSAGE from the landlocked inlet to the Telthearna bent so sharply that it was only just possible for a canoe to negotiate it. The rocky spurs on either side overlapped, closing the inlet like a wall, so that from within nothing could be seen of the river beyond.

The little bay, running inland between its paved shores, ended among colored water lilies at the outfall of the channel by the Tereth stone. Waiting with Melathys while the servants loaded the canoes, Kelderek gazed upward, past the bridge which he had crossed the night before, to where the Ledges opened above, their shape like that of a great arrowhead lying point downward on the hillside between the woods. The stream, he saw, was no longer flowing over them: it must have returned, during the night, to its normal course. High up, he could make out the figures of girls stooping over hoes and baskets, weeding and scouring among the stones.

When the loading of the canoes had begun, the sun had not yet reached this north-facing shore, but now it rose over the Ledges and shone down upon the inlet, changing the opaque gray water to a depth of slow-moving, luminous green. Sharp shadows fell across the pavements from the small stone buildings standing here and there along the edges, some secluded among the trees, others in the open among grass and flowers.

He wondered how old these buildings might be. There was none such on Ortelga. The whole place could be the work only of people long ago. What sort of people could they have been, who had constructed the Ledges?

Watership Down

Watership Down Tales From Watership Down

Tales From Watership Down Maia

Maia The Plague Dogs

The Plague Dogs Shardik

Shardik Traveller

Traveller The Girl in a Swing

The Girl in a Swing The Day Gone By

The Day Gone By Daniel

Daniel The Plague Dogs: A Novel

The Plague Dogs: A Novel